ST. MACARIUS THE GREAT "Seek Not the Praises of Men"

This selection is from St. Macarius the Great, born around 300 A.D. A former camel driver and trader, he was one of the earliest pioneers of "Scetis," an area in the Egyptian desert near Alexandria that is renowned for the richness of its ascetic life. St. Macarius lived before monasteries were established and as with many monks of his time was a wanderer, not living in any particular place for very long. He visited St. Anthony the Great in the Red Sea Desert at least twice. St. Macarius died around 390 A.D.

BEGIN: A brother came to see Abba Macarius the Egyptian, and said to him, "Abba, give me a word, that I may be saved." So the old man said, "Go to the cemetery and abuse the dead." The brother went there, abused them and threw stones at them; then he returned and told the old man about it. The latter said to him, "Didn't they say anything to you?" He replied, "No."

The old man said, "Go back tomorrow and praise them." So the brother went away and praised them, calling them, "Apostles, saints, and righteous men." He returned to the old man and said to him, "Did they not answer you?" The brother said, "No."

The old man said to him, "You know how you insulted them and they did not reply, and how you praised them and they did not speak; so you too, if you wish to be saved, must do the same and become a dead man. Like the dead, take no account of either the scorn of men or their praises, and you can be saved." END

from "The Desert Christian," by Sr. Benedicta Ward, (New York: MacMillan, 1975), p. 132

_____________________________________________________________________________________

ST. MARY OF EGYPT An Example of Repentance for Today

Now that we are in the season of fasting (Great Lent), our thoughts are turned toward repentance and one of the best examples of repentance for us is that of St. Mary of Egypt. In the usual versions of St. Mary's life, she is a repentant prostitute who spends most of her life in the desert, living alone in repentance. There is another, lesser known, version of her life, though, which is also worth reading and was commonly known among the ancient Desert Fathers. We will give both those versions, both instructive, which do not necessarily contradict each other. First, the more commonly-known version:

BEGIN: In her youth, Mary chose to live a dissolute life in Alexandria until, one day, drawn by curiosity, she joined some pilgrims going by ship to Jerusalem. On the way she seduced many of her companions, and continued to live in this way in Jerusalem. On the day appointed for the veneration of the Holy Cross (September 14), Mary went with the others to the door of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher where the relic of the True Cross was to be displayed. She went forward to enter the church with the other pilgrims, but on the threshold an invisible force seemed to prevent her from entering. At once sudden contrition filled her heart and she began to weep, praying to Mary the Mother of God to help her. Next morning she found she could enter the church and venerate the cross. At once she left the city and crossed over Jordan, taking only a little bread which she had bought with some coins a pilgrim had given her. In the desert she lived for forty seven years until a priest, Zossima, found her by accident, heard her story, gave her communion and eventually returned in time to bury her, a lion helping him to dig her grave. END

In the second version of her life, St. Mary did not immediately leave Jerusalem after consecrating herself to God, but instead stayed on at the Holy Sepulchre as a nun where she again fell into sin:

BEGIN: An anchorite told this story to the brothers: "When I was living in the desert on the slopes of Arnona, one day a weakness of soul came upon me and my thoughts said to me, "Go for a walk in the desert." I came to a dried up stream; it was an advanced hour in the evening and by the light of the moon I fixed my eyes on a distant object and I saw that it was sitting on a rock. Then I reflected that even if it was indeed a lion, I ought not to be afraid but to entrust myself to the grace of Christ. So I approached the rock, and by the side of it there was a narrow opening. At once the being I had seen afar off hid itself in this cave. When I reached the top of the rock, I found there a basket full of bread and a jar of water which showed me that it must be a human being. I called to him, 'Servant of God, be so kind as to come out so that I may be blessed by you.' He was silent but when I had renewed my appeal several times, he answered me thus: "Excuse me, father, but I cannot come out." When I asked why, he said, "You must know that I am a woman and that I am naked." At these words I rolled up the cloak that I was carrying, and threw it into the opening in the rock, saying to her, ìHere, cover yourself and come out" and she did so. When she had come out, we offered a prayer to God and we sat down. Then I asked her, "My mother, of your kindness, tell me what has happened to you. How long have you been here? Why did you undertake this journey? And how did you find this cave?"

She began to tell me about herself thus: "Once I was a consecrated virgin living in the Holy Sepulchre. One of the monks who had his cell at the gate got to know me. I used to meet him so often that it reached the point where we fell into sin. I would go to his house and he would come to mine. One day as I was was going to his cell as usual I heard him weeping before God and making his confession to Him. I knocked on the door, but he, because of hwat he had done with me, did not open it to me at all. He went on weeping and confessing. Seeing this, I said to myself, 'He is repenting of his sins but I do not repent of mine. He is lamenting his faults; shall I not also afflict myself?' Re-entering my cell alone, I dressed myself poorly and filled this basket with loaves and this jar with water, and then I went into the Holy Sepulchre. There I prayed asking that the great God, the wonderful, who came to save those who were lost and to raise up those that are fallen, He who hears all those who address themselves to Him in truth, that He would show mercy towards me, a sinful woman, and if He should find the repentance and transformation of my soul acceptable, that He would bless these loaves and this water so that they would last me to the end of my life, so that no necessity of the flesh or needs of hunger should give me a pretext for interrupting perpetual praise. After that I went into Holy Golgotha where I offered the same prayer and touching the top of the Holy Stone, there I invoked the holy Name of God. Then having reached Jericho and crossed over Jordan, I journeyed the length of the Dead Sea, for at that time the water was not very high. I crossed the mountains and wandered in the desert and I had the good fortune to find this dried up stream. When I climbed this rock, I found this cave here and when I went into it its narrowness pleased me greatly, for it made me think that the good God had offered it to me as a place of refuge. I have been here thirty years without having seen anyone except yourself at this hour. The basket of loaves and the jar of water have sufficed for my needs until now without failing me. After a time my clothes wore out but my hair had grown and I was covered with it in such a way that neither heat nor cold made me suffer by the grace of Christ."

After these words she invited me to take some of the loaves, for she sensed that I was very hungry. We ate and drank equally. Once, I looked into the basket and saw that the loaves remained as they had been and also the water had not diminished and I praised God. I wanted to leave her my old robe but she would not have it. She said, ìYou will bring me new clothing,î which pleased me very much and I begged her to wait for me just there. We offered a prayer to God and I went away, marking all the way my path for my return. I went back to the church of the nearby village and old the priest about the matter. He told the faithful that certain of the saints were living naked and that those who had too many clothes should offer them to them. The friends of Christ gave many clothes diligently and I took what was necessary and went off joyously in the hope of seeing again this spiritual mother. But I could not find the cave again although I wore myself out seeking it. And when at last by chance I saw it, the woman inspired by God was no longer to be found there; her absence affected me deeply. Some days later some anchorites came to visit me, and they told this story:

"When we came to the edge of the sea, we saw by night in the desert an anchorite whose hair covered him; when we begged him to bless us, he fled quickly, entering a little cave which we found nearby. We wanted to go in but he implored us, saying, 'Oh servants of Christ, do not disturb me! Lo,

on top of the rock is a basket of loaves and a jar of water; please be good enough to serve yourselves.' He offered a prayer for us to God, and when we reached the top we found things as he had said. We sat down and although we ate, the bread did not diminish, and although we drank of the water in the jar it remained the same. For the rest of the night we were silent. At dawn we got up to be blessed by the anchorite and we found him asleep in the Lord. Also, we discovered that he was a woman who had been naked and who had covered herself with her hair. We received a blessing from her body and rolled a stone to the entry, to the cave. Then, having offered a prayer to God, we came away."

Then I understood that he spoke of the holy mother, the former consecrated virgin, and I told them what I had learned from her. Together we glorified God to whom be glory to ages of ages. Amen. END

from Sr. Benedicta Ward, "Harlots of the Desert,"(Kalamazoo, Michigan: Cistercian Publications, 1987), pp. 27, 29 - 32.

___________________________________________________________________________________

ST. JOHN THE DWARF Life and Teachings: Part I

Today we will begin a two-part study of the life and teachings of St. John the Dwarf who was born in Egypt about 339. At the age of 18, he left for Scetis and was trained there by Abba Ammoes for twelve years. One of the most vivid characters in the Egyptian Desert, he attracted many disciples and in order to preserve his own solitude, he dug himself a cave underground. Abba John was later ordained priest and the number of his sayings that are recorded and preserved point to his importance among his disciples. After 407, he went to Suez and the Mountain of St. Anthony.

BEGIN: It was said of Abba John the Dwarf that he withdrew and lived in the desert at Scetis with an old man of Thebes. His abba, taking a piece of dry wood, planted it and said to him, "Water it every day with a bottle of water, until it bears fruit." Now the water was so far away that he had to leave in the evening and return the following morning. At the end of three years the wood came to life and bore fruit. The old man took some of the fruit and carried it to the church saying to the brethren, "Take and eat the fruit of obedience."

It was said of Abba John the Dwarf, that one day he said to his elder brother, "I should like to be free of all care, like the angels who do not work, but ceaselessly offer worship to God." So he took off his cloak and went away into the desert. After a week he came back to his brother. When he knocked on the door, he heard his brother say, before he opened it, "Who are you?" He said, "I am John, your brother." But he replied, "John has become an angel, and henceforth he is no longer among men." Then the other begged him saying, "It is I." However, his brother did not let him in, but left him there in distress until morning. Then, opening the door, he said to him, "You are a man and you must once again work in order to eat." Then John made a prostration before him, saying, "Forgive me." (NOTE: this story is, according to most sources, from Abba John's youth when he was still living with his family)

Abba John the Dwarf said, "If a king wanted to take possession of his enemy's city, he would begin by cutting off the water and the food and so his enemies, dying of hunger, would submit to him. It is the same with the passions of the flesh; if a man goes about fasting and hungry the enemies of his soul grow weak."

Some old men were entertaining themselves at Scetis by having a meal together; amongst them was Abba John. A venerable priest got up to offer drink, but nobody accepted any from him, except John the Dwarf. They were surprised and said to him, "How is that you, the youngest, dared to let yourself be served by the priest?" Then he said to them, "When I get up to offer drink, I am glad when everyone accepts it, since I am receiving my reward; that is the reason, then, that I accepted it, so that he also might gain his reward and not be grieved by seeing that no one would accept anything from him." When they heard this, they were all filled with wonder and edification at his discretion.

The brethren used to tell how the brethren were sitting one day at an agape* and one brother at table began to laugh. When he saw that, Abba John began to weep, saying, "What does this brother have in his heart, that he should laugh, when he ought to weep, because he is eating at an agape?"

Some brethren came one day to test him to see whether he would let his thoughts get dissipated and speak of the things of this world. They said to him, "We give thanks to God that this year there has been much rain and the palm trees have been able to drink, and their shoots have grown, and the brethren have found manual work." Abba John said to them, "So it is when the Holy Spirit descends into the hearts of men; they are renewed and they put forth leaves in the fear of God."

Abba John said, "I am like a man sitting under a great tree, who sees wild beasts and snakes coming against him in great numbers. When he cannot withstand them any longer, he runs to climb the tree and is saved. It is just the same with me; I sit in my cell and I am aware of evil thoughts coming against me, and when I have no more strength against them, I take refuge in God by prayer and I am saved from the enemy."

Abba Poemen said of Abba John the Dwarf that he had prayed God to take his passions away from him so that he might become free from care. He went and told an old man this: "I find myself in peace, without an enemy," he said. The old man said to him, "Go, beseech God to stir up warfare so that you may regain the affliction and humility that you used to have, for it is by warfare that the soul makes progress." So he besought God and when warfare came, he no longer prayed that it might be taken away, but said, "Lord, give me strength for the fight."

The old man also said this to a certain brother about the soul which wishes to be converted, "There was in a city a courtesan who had many lovers. One of the governors approached her, saying, "Promise me you will be good, and I will marry you." She promised this and he took her and brought her to his house. Her lovers, seeking her again, said to one another, "That lord has taken her with him to his house, so if we go to his house and he learns of it, he will condemn us. But let us go to the back, and whistle to her. Then, when she recognizes the sound of the whistle she will come down to us; as for us, we shall be unassailable." When she heard the whistle, the woman stopped her ears and withdrew to the inner chamber and shut the doors." The old man said that this courtesan is our soul, that her lovers are the passions and other men; that the lord is Christ; that the inner chamber is the eternal dwelling; those who whistle are the evil demons, but the soul always takes refuge in the Lord.

One day when Abba John was going up to Scetis with some other brothers, their guide lost his way for it was night time. So the brothers said to Abba John, "What shall we do, Abba, in order not to die wandering about, for the brother has lost the way?" The old man said to them, "If we speak to him, he will be filled with grief and shame. But look here, I will pretend to be ill and say I cannot walk any more; then we can stay here till the dawn." This he did. The others said, "We will not go on either, but we will stay with you." They sat there until the dawn, and in this way they did not upset the brother. END

*agape: the primary meaning of this Greek word is "love." Here, it refers to the common meal taken by the fathers after the celebration of the Liturgy. It can also refer to the Liturgy itself.

from Sr. Benedicta Ward, "The Sayings of the Desert Fathers," (Kalamazoo, Michigan: Cistercian Publications, 1975), pp. 85-89

___________________________________________________________________________________

ST. JOHN THE DWARF Life and Teachings: Part II

Today we will continue our two-part study of the life and teachings of St. John the Dwarf who was born in Egypt about 339. At the age of 18, he left for Scetis and was trained there by Abba Ammoes for twelve years. One of the most vivid characters in the Egyptian Desert, he attracted many disciples and in order to preserve his own solitude, he dug himself a cave underground. Abba John was later ordained priest and the number of his sayings that are recorded and preserved point to his importance among his disciples. After 407, he went to Suez and the Mountain of St. Anthony.

BEGIN: There was an old man at Scetis, very austere of body, but not very clear in his thoughts. He went to see Abba John to ask him about forgetfulness. Having received a word from him, he returned to his cell and forgot what Abba John had said to him. He went off again to ask him and having heard the same word from him, he returned with it. As he got near his cell, he forgot it again. This he did many times; he went there, but while he was returning he was overcome by forgetfulness. Later, meeting the old man he said to him, "Do you know, Abba, that I have forgotten again what you said to me? But I did not want to overburden you, so I did not come back." Abba John said to him, "Go and light a lamp." He lit it. He said to him, "Bring some more lamps, and light them from the first." He did so. Then Abba John said to the old man, "Has that lamp suffered any loss from the fact that other lamps have been lit from it?" He said, "No." The old man continued, "So it is with John; even if the whole of Scetis came to see me, they would not separate me from the love of Christ. Consequently, whenever you want to, come to me without hesitation." So, thanks to the endurance of these two men, God took forgetfulness away from the old man. Such was the work of the monks of Scetis; they inspire fervor in those who are in the conflict and do violence to themselves to win others to do good.

Abba John said, "Who sold Joseph" A brother replied saying, "It was his brethren." The old man said to him, "No, it was his humility which sold him, because he could have said, "I am their brother" and have objected, but, because he kept silence, he sold himself by his humility. It is also his humility which set him up as chief in Egypt."

He also said, "Humility and the fear of God are above all virtues."

It was said of Abba John that when he went to church at Scetis, he heard some brethren arguing, so he returned to his cell. He went round it three times and then went in. Some brethren who had seen him, wondered why he had done this, and they went to ask him. He said to them, "My ears were full of that argument, so I circled round in order to purify them, and thus I entered my cell with my mind at rest."

On day a brother came to Abba John's cell. It was late and he was in a hurry to leave. While they were speaking of the virtues, dawn came without their noticing it. Abba John came out with him to see him off, and they went on talking until the sixth hour. Then he made him go in again after they had eaten, he sent him away. (EDITOR: Isn't this a wonderful story?! How these Holy Men loved to talk about the spiritual life!)

One day a brother came to Abba John to take away some baskets. He came out and said to him, "What do you want, brother?" He said, "Baskets, Abba." Going inside to bring them to him, he forgot them, and sat down to weave. Again the brother knocked. When Abba John came out, the brother said, "Bring me the baskets, Abba." The old man went in once more and sat down to weave. Once more the brother knocked and, coming out, Abba John said, "What do you want brother?" He replied, "The baskets, Abba." Then, taking him by the hand, Abba John led him inside, saying, "If you want the baskets, take them and go away, because really, I have no time for such things."

A camel driver came one day to pick up some goods and take them elsewhere. Going inside to bring him what he had woven, Abba John forgot about it because his spirit was fixed in God. So once more the camel driver disturbed him by knocking on the door and once more Abba John went in and forgot. The camel driver knocked a third time and Abba John went in saying, "Weaving - camel; weaving - camel." He said this so that he would not forget again.

An old man came to Abba John's cell and found him asleep, with an angel standing above him, fanning him. Seeing this, he withdrew. When Abba John got up, he said to his disciple, "Did anyone come in while I was asleep?" He said, "Yes, an old man." Then Abba John knew that this old man was his equal, and that he had seen the angel.

Abba John said, "I think it best that a man should have a little bit of all the virtues. Therefore, get up early every day and acquire the beginning of every virtue and every commandment of God. Use great patience, with fear and long-suffering, in the love of God, with all the fervour of your soul and body. Exercise great humility, bear with interior distress; be vigilant and pray often with reverence and groaning, with purity of speech and control of your eyes. When you are despised do not get angry; be at peace, and do not render evil for evil. Do not pay attention to the faults of others, and do not try to compare yourself with others, knowing you are less than every created thing. Renounce everything material and that which is of the flesh. Live by the cross, in warfare, in poverty of spirit, in voluntary spiritual asceticism, in fasting, penitence and tears, in discernment, in purity of soul, taking hold of that which is good. Do your work in peace. Persevere in keeping vigil, in hunger and thirst, in cold and nakedness, and in sufferings. Shut yourself in a tomb as though you were already dead, so that at all times you will think death is near."

One of the fathers asked Abba John the Dwarf, "What is a monk?" He said, "He is toil. The monk toils at all he does. That is what a monk is."

Abba John the Dwarf said, "A house is not built by beginning at the top and working down. You must begin with the foundations in order to reach the top." They said to him, "What does this saying mean?" He said, "The foundation is our neighbor, whom we must win, and that is the place to begin. For all the commandments of Christ depend on this one."

Abba John said to his brother, "Even if we are entirely despised in the eyes of men, let us rejoice that we are honored in the sight of God."

Abba Poemen said that Abba John said that the saints are like a group of trees, each bearing different fruit, but watered from the same source. The practices of one saint differ from those of another, but it is the same Spirit that works in all of them. END

from Sr. Benedicta Ward, "The Sayings of the Desert Fathers," (Kalamazoo, Michigan: Cistercian Publications, 1975), pp. 89-95

___________________________________________________________________________________

POPE SHENOUDA III A Short History of Coptic Monasticism

Transcript of a Speech of His Holiness Pope Shenouda III,

Patriarch of Alexandria and the See of St. Mark

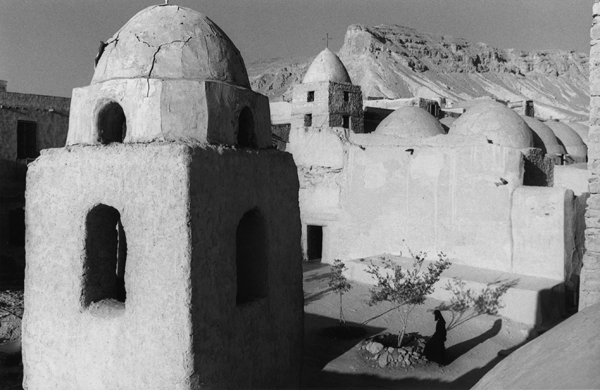

Delivered at the Opening of the Exhibit by photographer Michael McClellan, "A Still, Small Voice: Sixteen Centuries of Egyptian Monasticism," at the Washington National Cathedral, March 15, 1992.

I want to tell you now about Coptic monasticism. Egypt is considered the motherland of monasticism. The first monk in the whole world was St. Anthony, a Copt from Upper Egypt. He was born in the year 251 and departed in the year 356; he lived 105 years. During this period he established monasticism and all the leaders of monasticism in the whole world were his disciples or the disciples of his disciples.

Also, the first abbot in the world who established monasteries was St. Bakhum (Pachomius), also a Copt from Upper Egypt. He lived in the fourth century and at the end of the third century. When we say that St. Anthony was born in the year 251, that he became a monk when he was about twenty years old or less, and then spent the first thirty years in complete solitude, that means monasticism began in Egypt at the end of the third century or the beginning of the fourth century -- more than sixteen centuries.

Monasticism began in Egypt as a life of complete solitude, a life of solitude and contemplation. No one of our monks in the fourth century or the fifth century served the church in the world. They wanted to forget the whole world and to be forgotten by the world and to have only our Lord God in their thinking, in their emotions, to fill all their hearts and all their lives.

So, when monasticism began it did not begin in monasteries, it began in caves scattered through the mountains, and holes in the ground, and some dwelling places. But afterwards, they began to build monasteries. Monasteries were built in the midst of the fourth century, or perhaps some years before. The monasteries of Upper Egypt, of St. Bakhum, had many monks living in them, living together a life called in the Greek language, "kenobium," which means "life together." And that was a characteristic of the monasteries of Upper Egypt of St. Bakhum and St. Shenouda.

But in Wadi Natrun, the monasteries had a special characteristic. The monasteries were built in the most ancient places and had churches and the refectory. The monks used to go to the church once every week on Saturday evening to have a kind of spiritual teaching by the elders, with any question or problem being said by the monks -- who were called brothers at that time -- with the answers being given by the elders. They used to celebrate the Holy Communion on Sunday morning and then eat together in the refectory; then each monk would leave the monastery to live his own life of solitude until the next week. That means they used to gather together only once, one day every week, and live the rest of their lives in complete solitude. Why? They wanted to purify their minds from anything of worldly thinking, not to think of the world any longer, not to have news from the world, not to have letters from the world, not to read newspapers, even not to receive visitors.

But at last, this light of monasticism could not be hidden. Many people came from abroad to hear a word of benefit from those monks and these monks, the Coptic monks, the Egyptian monks, did not write about themselves, but the visitors who came wrote about them. One of the most famous was the Lausiac History by Palladius. It was called Lausiac History because it was written to a certain noble man named Lausius. This Lausiac History was translated into the English language with the title of "Paradise of the Fathers." This "Paradise of the Fathers" was known in the Arabic language as "Bustan al-Ruhaban." Another famous work was that of Rufinus about the desert fathers; another was by John Cassian who published two books, one called the "Institutes" and the other called "Conferences." In his book, "Institutes," he had twelve chapters, the first four about the history of Coptic monasticism, the life of monks and their way of life, and the other eight chapters about spiritual warfares which may attack monks; for example, pride, vainglory, anger, and so on.

He said the traveler who passed from Alexandria to Luxor had, on all the journey, the sound of hymns in his ears from Alexandria to Luxor. That means all along the River Nile; but he was speaking about the western desert. In the eastern desert of the Nile Valley, we have two famous monasteries, the Monastery of St. Anthony and the Monastery of St. Paul the Hermit. Those hermits were also called, in monastic life, anchorites. Anchorites. In the Arabic language, they were called "as-Sawah." They always used to live in caves very far from any monastery. When we read the story by St. Paphnutius who wrote for us the history or life of Abba Nofer, it was a trip of nearly thirty days in what was called the "inner wilderness." They lived in a place quite unknown to anybody.

For example, St. Paul the hermit lived about eighty years in monasticism and did not see the face of any human being. Many other hermits -- for example St. Caras -- lived about 60 years in monasticism without seeing the face of any human being. They forgot all about the world, they had nothing in their memory about the world or its news. Their senses could not collect any worldly matter, they had only God and His Love in their memory, in their mind, in their hearts, and in their emotions. They could fulfill the biblical verse which was written in Deuteronomy 6, and also was said by our Lord Jesus Christ in Matthew 21, "to love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, with all thy mind, with all they soul, and with all thy power." How can a person give the whole of his mind to the Lord God? How? How to give the whole of your heart? We may love God through loving human beings, but those hermits, those anchorites, had only God in their minds. They could not think about any other matter.

Now, for example, when we speak to youth classes, we say to youth that bad thoughts are thoughts of any kind of sin; but for these monks, bad thoughts were thoughts of any matter besides God. For this reason, they were called "earthly angels," or "angelic human beings." They lived as angels on the earth, but as you know from biblical studies, we have two kinds of angels. (The first kind is) angels who live all their time praising God: for example, the seraphim. Those angels of the seraphim are mentioned only in Isaiah 6; they always were singing "agios, agios" or "holy, holy, holy" praising the Lord. But we have another kind of angel which was mentioned in the Epistle to the Hebrews, chapter 1, verse 14. They are ministering spirits sent to those who are called for salvation. We can call the pastors of the church, the ministers of the church, angels sent to the world to serve the world of salvation; for example, the pastors of the seven churches in Asia were also called angels -- the angel of Ephesus, the angel of Smyrna, the angel of Pergamos, and so on. But, the angels who devoted all their time praising the Lord as the seraphim were the symbol of holy life put in front of those monks.

St. Athanasius of Alexandria was chosen to be the 20th Pope of the See of St. Mark in the year 328 or 329, while he was only a deacon. At that time St. Anthony was living and was his spiritual father. But St. Anthony was not chosen to be the pope or patriarch; instead, they chose the deacon Athanasius. Through the flourishing era of monasticism of the fourth century, the fifth century, and the first half of the sixth century, they did not choose these monks to be bishops or patriarchs because those monks preferred to have a life of solitude, a life of prayer, a life of contemplation. They preferred to live with God, not with human beings. They preferred to be remembered only by God, not by human beings. Why? Because sometimes if they permitted visits they could lose their life of solitude and prayer, their prayers would be interrupted, and their meditation of God would be interrupted.

A story that was mentioned in the "Paradise of the Fathers" was that a certain monk was walking in the wilderness and two angels came beside him. He did not look to the right or to the left, but said, "I do not want even angels interrupting my meditation of God," remembering what was in the Epistle to the Romans, chapter 8 (verses 38 and 39).

At last, the Church was in need of those people and then bishops were taken from among monks of the deserts and then patriarchs and then the great need of the Church was for some of them to work as priests, as pastors. Then the life of complete solitude became a minority in our monasteries. . . . Remember two verses in the Bible; I do not know how you comment on these verses. The verse in St. Luke's gospel, chapter 18, verse 1 ("And he spake a parable unto them to this end, that men ought always to pray, and not to faint."), and also another verse, "Pray without ceasing," in the First Epistle to the Thessalonians, chapter 5, verse 17. Pray without ceasing, without interruption. How can we fulfill these verses?

We have to fulfill the symbol of Mary, not the symbol of Martha. The symbol of Martha is working for the service of God Himself; but for Mary, it is to be only looking at God, contemplation, prayer, to be at His own feet, listening to His words, and contemplating His words. So at least we should have a small number of these monks representing that life of the past and to be a blessing for the world and to bless the world. When our Lord God wanted to burn Sodom . . . He said even if I find only ten pure persons in the city, I will not burn the city. To have these persons only existing. He did not say if ten persons pray for this city -- only that if there are only ten persons I will not burn the city. Those monks were a kind of blessing to the world representing pure life, the purest life in the whole world, resembling persons who don't love anything in the world -- even themselves -- but only God to be kept in mind.

Now in Egypt we are trying to let monastic life return to many deserted monasteries. We had hundreds of monasteries in the past. We are now working in the White Monastery of St. Shenouda, in the Red Monastery in front of this white one, and in about four monasteries in the mountain of Akhmim, trying to send monks to this area to let monastic life return. . . . If you come (to visit our monasteries), you will be deeply welcomed and you will see something about the ancient monastic life and the expansion of monasticism today. I myself, in only the single monastery of Anba Bishoi, ordained about 150 monks, new monks. For this reason, we had to build many new cells in the monasteries to receive those new novices who want to prepare themselves for monasticism. Also, in every monastery now we have a retreat house for those youth who want to come to the monastery to spend some days of spiritual experience under spiritual guidance. Some of them like monastic life and become monks.

We have great work in Sunday schools. In Sunday schools we prepare the children from the very beginning of their lives to live a spiritual life, to live in the Lord, some of these children join the seminary, some become Sunday school teachers, and some of those Sunday school teachers join the seminary. And when they graduate from the university and the seminary and Sunday school, they go to the monasteries to become monks -- some of them -- and some of them become parish priests. So, through the revival of Sunday schools we prepare a great number of persons to be monks. To live a spiritual life for their own benefit is all right; if the church needs some of them to serve, that is all right.

We don't oblige any monk to lead a certain life. For he who wants to live in the monastery as part of the congregation, that is all right. If he wants to lead a life of solitude inside the monastery, that is all right. If he wants a cell of solitude outside the monastery or on the near hills, that will be all right. He who wants to live in a cave will have the permission to live in a cave. We have all kinds of monasticism.

___________________________________________________________________________________

At times when things become frightening, when we are anxious and afraid, we are comforted to know that prayers are always being said in the Orthodox monasteries, the Rt. Rev. John Abdalah, spiritual advisor to the North American Board of Antiochian Women, told the group at their last meeting.

At times when things become frightening, when we are anxious and afraid, we are comforted to know that prayers are always being said in the Orthodox monasteries, the Rt. Rev. John Abdalah, spiritual advisor to the North American Board of Antiochian Women, told the group at their last meeting. In recent years many Orthodox monasteries have been started in this country. In all, there are 99 monasteries in the United States and 11 monasteries in Canada, according to the Orthodox Monasteries Worldwide Directory, found online.

In recent years many Orthodox monasteries have been started in this country. In all, there are 99 monasteries in the United States and 11 monasteries in Canada, according to the Orthodox Monasteries Worldwide Directory, found online.